Madagascar: Out of Time

(A version of this story was first published in Boards, 2014 Autumn Issue.)

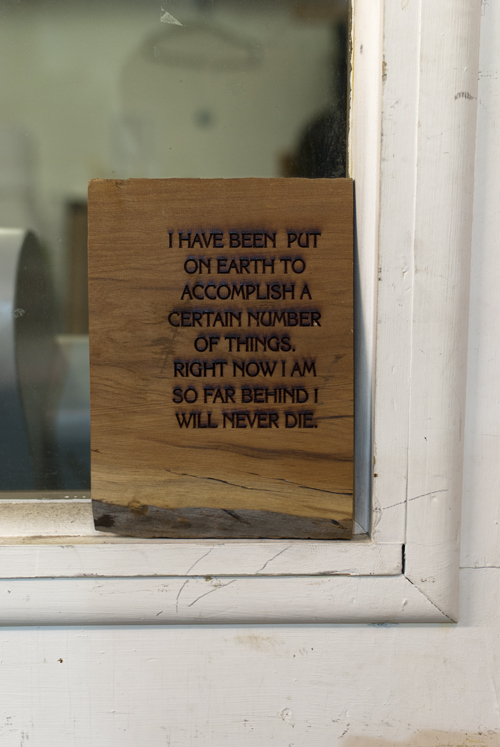

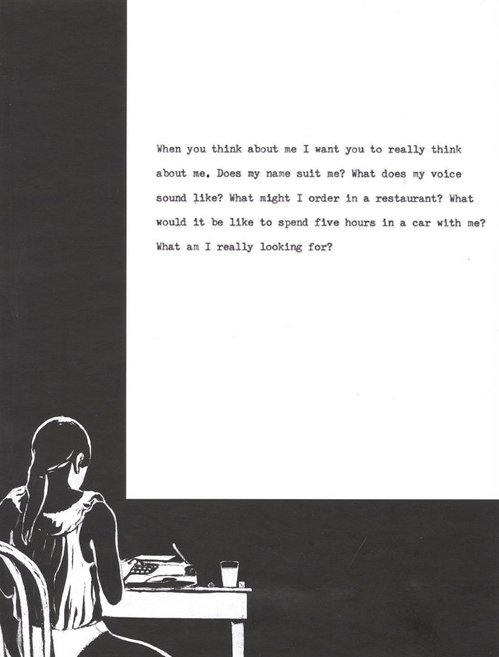

I’m sitting in a friend’s Hamburg apartment off the Alster, eating her marzipan and licorice even though I should be writing about a trip I did almost a year ago to Madagascar. The deadline for this essay is over a week past, and I am afraid that my editor will not publish this, but I cannot stop writing. I must finish this essay because my mind won’t be free until Madagascar–a trip that was so full of difficulties (even now!)—is finished once and for all.

I look outside of the 5th floor window down on the German city streets, and I see cafes serving coffee, I see people walking with purpose, and I see time embedded into the souls of the trees and the souls of the buildings and the souls of the people. Put your ear against the soul of a German man (or lady), and you will hear the ticking of time—like a heartbeat but more steady. Einstein says time is relative, but here in Germany, time is nothing but a fact. No matter where you stand, you can see a clock in every train station or airport.

This means that I have a perfect vantage point of the time passing by me while I sit not writing. I can see the clock tock 4 o’clock in the afternoon, which is my self-imposed deadline for the day’s writing. But now, 4pm is just another time in the past. The clock continues forward while my Madagascar article simply does not.

For this three thousand word article, I have about six thousand words thrown into a Word document, portraying a Pollock painting of experiences from my trip. There is no through-line, and there is no order: just moments unlinked.

Now it is midnight, but I’m not tired—I don’t feel tied to time anymore. As a pro windsurfer, I go through time-zones like popcorn. Hawaii to Europe is a 12-hour time difference, but for me, the trip is a standard commute to compete. I try not to think about this and instead focus back to Madagascar, where I went to make a film but instead discovered a new world. Ignoring my mess of 6 thousand words, I try to start over. Go back to zero. Hit reset on the clock. Except you can’t. Life only goes faster and faster and faster forward. Thinking back:

Madagascar does not have many roads; and the asphalt that does exist is so potted that the dirt is preferred. Madagascar does not have hot water; I stayed with a wealthy local family and faced a cold shower after every day of windsurfing. Madagascar is for manpower; lawns are cut with shears, and gravel comes from hammers. And WIFI? Forget about it. But the biggest lacking luxury of all was Time. Madagascar does not even have time.

What does it even mean that Madagascar is without time? For starters, without time there can be no death. Obviously, people die, but the Malagasy people do not see this as a stop. In the interior of the island, the Malagasy annually dig up the bodies of their ancestors, put new clothes on the corpses, and re-bury the newly dressed skeletons.

Even the Malagasy language lacks time. “Good morning”, “good afternoon”, “good evening”, “good anytime” are all represented by the same phrase: “M’bola tsara”, which translates to something like “still good?” The response is the same as the question: M’bola tsara. Still good. Nothing changes. M’bola tsara.

On my first day in Mada, I saw a young Zebu (a Malagasy horned cow) sacrificed on the beach in front of the house where I stayed. The poor calf was sailed in from across the bay with its skinny legs tied together. When put on the sand, he shook from seasickness or from cold or from terror—or from some bovine Parkinson’s, who knows.

The local people stuck money to the Zebu’s hide with honey as they said wishes to go with the Zebu to the spirit world. The beast was then beheaded and butchered in the sand. The son of my host family, Billy, placed the skull on a sacred tree that holds the spirits of his ancestors.

I felt pity for the animal, but my new Malagasy family reassured me that in Madagascar death is not the end. Rather, the sacrifice delivers the Zebu to the spirit world of the ancestor spirits. The dead Zebu’s blood pooled in the sand, and opened intestines stank. The tide rose and took away the blood and dung. We ate fresh Zebu steak that night. M’bola tsara.

The exception that proves the rule regarding Madagascar and time is my host-brother Billy’s Casio wristwatch, which he loved and wore everywhere despite not having a job or going to school or living in a place that even has time. During the sacrifice, which was done mainly to wish him well during his next year in university, he somehow broke the plastic strap to his Casio. He looked down at the white stripe of skin on his brown arm and nearly cried. This was a disaster as terrible as Prometheus tripping down Mt Olympus on his way to gift fire to man and losing the torch in the dirt, extinguishing the flame forever.

Time is like that fire. Time is a sign of the west and the power and wealth it represents. Time is a sign of progress, or rather time allows for the concept of progress. Owning time then is a symbol of power.

At one point, in a small village, we sought permission to windsurf and film where no one had ever windsurfed before. This village was way out in the Bush hours from any road. We were told: You know when you go into the Bush but you don’t know when you’ll return, so eat a big breakfast, you might be glad you did.

An often said Malagasy phrase is “Mora Mora” which means “Slowly Slowly.” This can be a response to anything. How’s it going? Mora Mora. How is writing that story on Madagascar? Mora Mora. How long does it take to reach the village? Mora Mora.

The village was the cliché picture of African village life. Chickens pecked the dust. Zebu wandered slowly, aimlessly. A mutt bitch with her worn tits full of pups lay—dead-looking—in the shade under a porch. One pup, white probably but dirt colored actually, with no room on the mother’s tits, wandered on top of the porch of the hut and into the open doorway, following the scent of food. The woman of the hut stood in the doorway, guarding her abode. She looked down at this pathetic baby dog searching for food (for life!), and without any hesitation, she gave it a full football kick. The puppy twirled and flipped through the air before landing in a whimper and plume of dust—scampering back to the frenzy at the tits. M’bola tsara.

The hut of the village leader has two rooms while most of the other huts have just one room for the entire family. I needed his permission to film from the island off the coast from this village. My crew and I sat behind Billy as he described what we wanted.

The conversation commenced in Malagasy, so instead of listening, I scanned the walls with my eyes. The wood walls were mostly bare except for two plastic clocks. The hands on each clock showed a different time, and as I stared longer, I realized that both were stopped. Mora Mora.

I asked Billy to ask the significance of the times on the clocks. I thought of all sorts of possibilities: maybe these were the times his children were born? The answer was: no significance to the times of the stopped hands on the two clocks on his otherwise bare wall. The clocks were only decorative. M’bola tsara.

The lack of Time meant that our minds were 100% with our bodies, which in this age of constant communication is almost impossible. I could not think to another place or time. Time zones only matter after the advent of instant communication, which starts with the telegraph. Before the telegraph and with such long travel times between places, time zones were an incomprehensible concept. But once someone in London could send a message as the sun sets to New York where the sun still rides high in the sky, time zones matter. Time zones allow for coordinated, long-distance mass transit and stock exchanges and so many things. The telegraph became the telephone which became the iPhone. But this history does not apply in Madagascar.

In Madagascar, I had no communication with anyone farther away than I could shout. I lost a girlfriend on that trip because I did not call her after she suffered a surfing accident. I could not call her to explain that I could not call her. M’Bola Tsara.

This 100% in-the-momentness was possibly the reason the beauty of the landscape assaulted me so powerfully. Normally beauty has a tendency to bore, which is why locals never notice “the view” and why tourists crave home or the hotel TV after a week. Maybe this is why the cruise or bus tour is so common—in a state of perpetual motion, you exist in a state of constant newness, never actually being in any one place long enough to be bored. Not so in Madagascar.

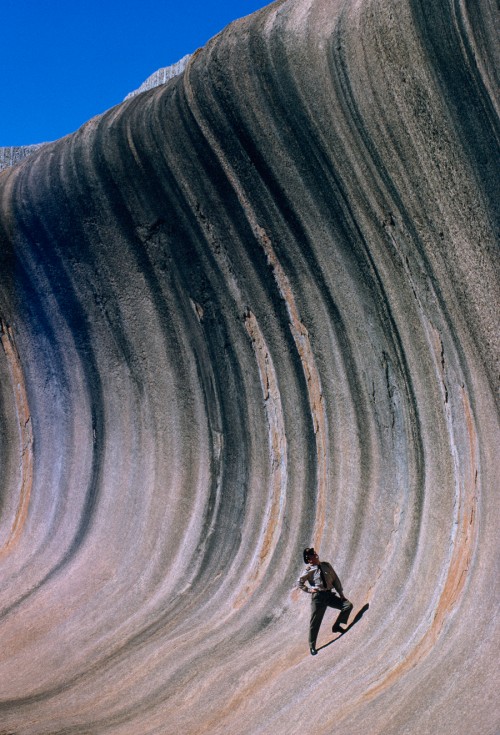

The beauty of Madagascar violently dominates the viewer. The view here does not rest passively while you sit with toes in the sand and a Caipirinha in hand. The Malagasy wilderness consumes you. The waters of the Emerald Sea are a blue beyond the blues of Photoshop. Sailing through these sapphire seas feels fake and therefore dizzying. The black lava rock is so razor sharp that walking across is impossible without thick-soled shoes. The land is king and you are the view. M’bola tsara.

I am reminded of what D H Lawrence said of Australia a century ago:

“The land is here: sky high and blue and new, as if no one had ever taken a breath from it; and the air is new, strong, fresh as silver; and the land is terribly big and empty, still uninhabited…it is too new, you see: too vast. It needs hundreds of years before it can live. This is the land where unborn souls, strange and not to be known, which shall be born in 500 years, live.”

Here in Madagascar, the land will never be inhabited, not even in 500 years. It is too beautiful, too powerful. The inspiration for the man-eating tree in the Harry Potter books comes from Malagasy legends. Hiking the mountains and wilderness around Diego Suarez, Billy would point at some curled and twisted plant and comment: Don’t touch that tree or it will be bad for you; don’t even look at it. No other explanation.

Flying from the capital Antananarivo to the northern tip of the island, which is where we were, I could see green mountains—without any paths or people—that surely contain thousands plants and animals yet to be discovered by biology. This untouched land resists the human touch.

Even the bottled water tastes sea-like. More than just salty, the water tastes like seaweed but only faintly and not unpleasantly. So hidden is this taste that I would drink a sip and wonder whether it did in fact taste sea-y and then have to take another sip to find out. And then another. I drunk whole bottles of water this way.

Fresh water in Madagascar costs more than coca cola or beer (Three Horse Beer is the local brew on tap), but while water is rare, the land is rich in almost every other way: fresh vanilla, chocolate, cinnamon bark, pepper, oil, gold, etc. Most of these lie untouched in the virgin wild.

I became giddy to taste, touch, and take from Madagascar. I took bunches vanilla pods, ounces of black pepper, a rock of ambergris to take home in a bundle for free that would have cost over a thousand dollars if purchased at western prices. I wanted—I am ashamed to realize now—to exploit the unexploited land. I felt the greed of Columbus. The riches overflowed, and that was reason enough to take.

But not totally. You see, my trip was not one of hotels, but rather a Malagasy family adopted me. They heard that I wanted to do a film trip to Madagascar, and they invited my crew and me into their home.

On one of the many nights spent talking after a delicious dinner (Blue Mangrove Crab Salad is highly recommended), my host-mother Jacqueline told me the reason she invited me. Yes, her son Billy loves windsurfing and was elated to be part of our trip. But the real reason is more complex.

Jacqueline asked me if I saw the big sign that is impossible to not see when you step out of the airport. I blushed. Of course I saw the sign and wondered what “Say No to Sexual Tourism” meant. Jacqueline explained that old men from Europe (mainly France as Madagascar is a former French colony) fly to Diego Suarez for the teenage girls who are poor and uneducated. A few euros and presents later, an old man can have many teenage girlfriends.

Jacqueline wants a more positive kind of tourism for the northern tip of Madagascar—her homeland. She thinks windsurfing could be an answer because of the sandy beaches and nonstop wind and waves. She wants tourists that support and respect the local people instead of screwing them.

Now noticing the near-pedophilia everywhere, I felt dirty. For the first time in my life, I understood nudism—an escape from society. I wanted to travel this coast and to keep it untouched by the groping hand of humanity—even my own. But if I were to travel the coast naked (which I did not do) I would want one human item: my windsurfer so that I could fit myself into the wind and waves.

What an old wind! The oldest wind I’ve seen—it was endless like a long, infinitely long freight train that goes by car after car, stretching across the horizon. 25knots when I arrived till the day I left. In most places around the world, winds come and go. Some winds die in the night—like in Maui. I had a midnight session on the Emerald Sea during full moon. In Mada, the wind is immortal. M’bola tsara.

But despite this perfect wind and windswell, my job—getting windsurfing footage and photos—proved almost impossible. Something went wrong every single day.

I cannot catalog every near-disaster. The Emerald Sea and Bay of Sakalava both offer really consistent good windsurfing: starboard tack side-onshore with head high waves every single day. But the best spots for photos and film are more difficult to reach and surf. We needed a boat to get to most of the spots, but we never had the right boat. One of the boats capsized, throwing us into the swells. Babaomby Lodge made a deal with me for 3-day-use of a jet ski for filming but did not deliver. Some of the local French tried to sabotage my trip by spreading rumors in town that I was a fake pro windsurfer—an imposter not to be helped! Oh, and my photographer (flown in from San Francisco) wanted to windsurf instead of taking any photos—the waves and wind were too tempting.

The trip reminded me that adventure is hard. Nowadays, the word gets stuck to picnics and hikes, but classic adventure is miserable when you’re in it: what-the-hell-am-I-doing misery. Adventure is only fun as a memory.

Here’s an excerpt from my notes on the trip that captures an example of what each day felt like:

“With us so near the equator, the sun hangs on the top of the sky all day and then falls quickly down past the horizon so that the entire afternoon sprints by in not much more than an hour. Night and day exist but not the steady flow of time to which we nail our western lives. This means we have only about an hour of good light every day just before the dark of night.

Today, we spent the whole day till dark filming from a city-block-size uninhabited island made completely of the sharpest black lava rock I have ever seen. If lava dries quickly enough, it becomes the sharp edge of broken glass. Two kinds of bushes grow from this rock island– no trees. One is a shrub with inch long thorns that sprawls about the island like a thorny, bushy vine. And the other plant is green, leafless, and looks like it should grow underwater, like a sea anemone. This second plant breaks easily when walked through and spouts a milky sap.

After a day of filming from the island, the sun already set, and a treacherous 2-hour boat ride without lights ahead of us, we loaded the camera and windsurfing gear into the hull. All of us were covered in cuts and that milky sap. Once on the dangerous sea journey home, the skipper turned and said, “Don’t get the white stuff in your eyes or you’ll go blind.”

M’bola tsara.

——-

Thank you very much to everyone who made the trip possible. The Gaspard family welcomed me into their family and for that I am forever grateful. Billy and Madapower events took care of all local logistics. Andi Jansen and Ruben Lemmens were the fearless men behind the lenses during the adventure. This trip changed my life. Thank you all for making it happen.

UPDATE: The pictures are now clickable and lead to a larger version.